“I am the luckiest brewer in London,” beams John Hatch.

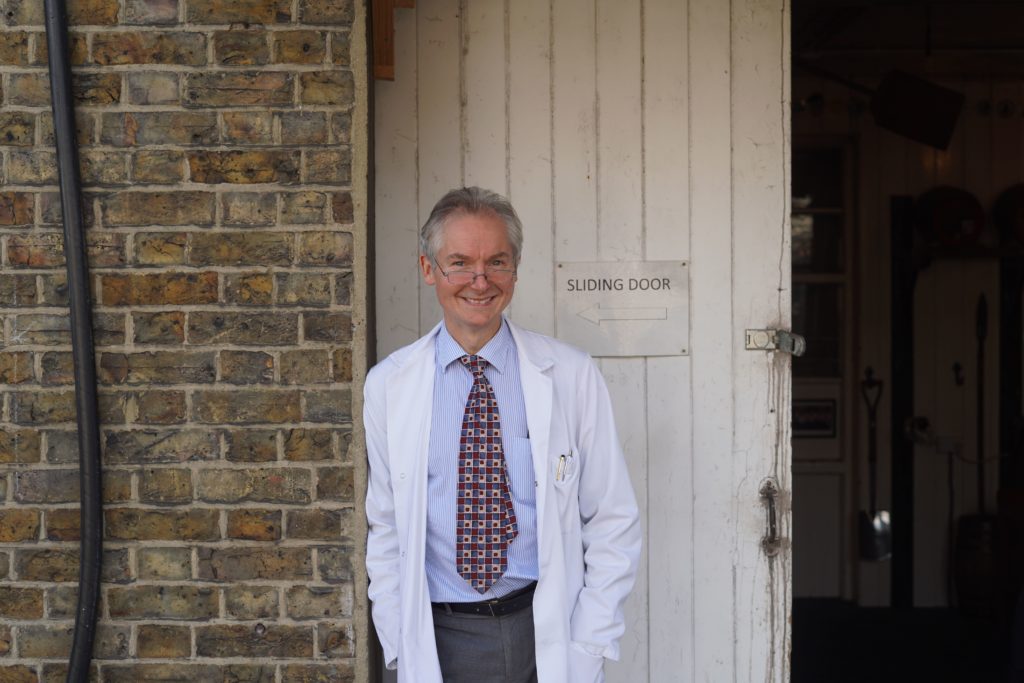

John is the head brewer at Wandsworth’s Ram Brewery. He’s also the assistant brewer, head cleaner, packaging operative and everything in-between.

You see, the Ram Brewery is no normal brewery. Instead, it’s a truly unique operation housed on the grounds of the old Young’s brewery. A passion project that came into being upon the news that Young’s was to shutter it’s London brewing business back in 2006, Hatch has ensured that although the brewery would be leaving the site, brewing wouldn’t.

In doing so, it has guaranteed that Wandsworth would maintain the proud mantle of being home to the longest uninterrupted period of continuous brewing in the UK. And for Hatch, who celebrated his 30th anniversary on site in September, it’s just the latest evolution of his love affair with Young’s and the brewing industry as a whole. Something that started many years ago.

“I was an underperforming school boy, to be honest. I was the prankster and trickster that teachers detested, and I don’t blame them,” he laughs. “Whether it was loosening a teacher’s bike seat, or lining their draw with a dozen snaps I removed from crackers, I’d be the one doing it.”

Comprehensive school followed and Hatch says he struggled along to get his A-Levels. The one subject of those that struck a chord, though, was Biology and a university degree at Bangor followed.

“I enjoyed it, but had no idea of the type of career path I wanted. At the same time, I realised I liked beer, and drank a lot of it!” he recalls.

Cask beer and Guinness were his fortes during education and Hatch even proudly held the record for knocking back a yard of famous Irish beverage.

“If you think the cascading effect you get in a pint is memorising, wait until you see it in a yard,” he enthuses. “It was memorising!”

But as his admiration for beer increased, his university grant went in the opposite direction, and Hatch realised his couldn’t afford to drink as much anymore. So wide-eyed, he journeyed to high street chain Boots and procured one of the home brew kits on offer.

“Those early attempts were not good, I’ll be the first to admit. But before long I was producing some quite cracking beers, and even some wine, too,” he recalls. “The only logical thing to do was throw parties on Sunday night and people would get trollied. I’d enjoy watching people enjoy the drinks I made and one day a friend, Richard, told me what I was doing was great and that I should be doing it for a living.”

He adds: “What a thought! It was inspirational to hear because before that, I had no idea what I was going to do for a living. And to work in beer was something I could definitely get on board with.

“So I returned home to Bristol in the summer of 1985 and headed straight to the public library to consult the Yellow Pages directory and write down the details of every brewery going. There was 423 of them at the time, I believe.”

Hatch wrote to these businesses to try and get that elusive first position in the industry. He was frank, telling each business that he was a student of Biology and wanted to brew beer for a living. Whitbread responded in kind thanking him for his letter and to get back to them the following year upon completion of his studies.

“So I did! I wrote back to Alastair Lever at Whitbread in Magor, Wales and he replied to tell me ‘See you Monday’. Simple as that!” he laughs.

Hatch joined Whitbread as a microbiologist on a three month contract in the run up to Christmas, helping oversea the integrity of a mammoth canning runs of beers such as Heineken and Stella Artois. It was during that time that he also joined the Brewers Guild. A body that offered training, talks and also helped match brewers with jobs in the industry.

It was a wise move.

The role, which was due to become permanent in the new year, never materialised. The closure of Whitbread’s Salford brewery resulted in an influx of staff being relocated in their roles.

“I was the last and the first out,” he says. “But they gave me a glowing reference and a month’s extra pay so off I went. During this time, I had learned about John Young and his brewery, Young’s based in London. He was a keen advocate for cask beer and way before CAMRA existed he was there on his soapbox declaring the benefits of cask over ‘fizzy, gassy keg’. I knew I wanted to work for him.”

Hatch left Whitbread and worked for six months in the NHS. It was here he received his beer equivalent of a golden ticket from Charlie and The Chocolate Factory. The request to interview for a job at Young’s.

“They told me they had found my details through the guild and have space for a microbiologist. I couldn’t believe it. So my dad zipped me down the M4 from Bristol to London. I vividly recall him pulling up into the chairman’s carpark and was swiftly b*llocked for parking there. He didn’t care. He went toe to toe with the person and informed them his son was there for an interview.”

Hatch passed the interview with head brewer Ken Don and laboratory chemist David Neal with flying colours. But he was barely through the door when an opportunity to become a junior brewer arose. And he took it with both hands, working under brewhouse manager at the time, Barry John. He learned a great deal with John but it was another figure that Hatch singles out for particular praise.

“It was at a Brewers Guild dinner when I was introduced to a gentleman named Derek Prentice. He knew I was at Young’s and informed me he’d be joining me at the business after Christmas,” says Hatch. “We were the new guys together but even then, he was vastly more experienced than me. Derek taught me a great amount and I’ve forgotten so much more than he ever taught me. He’s an amazing brewer and a fantastic person.”

Prentice, now head brewer at Wimbledon Brewery, is celebrating an incredible 50 years in the industry in 2018. Upon joining Young’s, Hatch recalls his skill at identifying problems but also a desire to not tread on anyone’s toes, either.

“Derek recommended that I was given various projects such as looking as dissolved oxygen between point A and point B. I was young, and available, so happily took these projects on. And each time, I’d find a problem that he knew was going to be there. He just wanted someone else to identify it and solve it,” says Hatch.

The quality of Young’s beer rocketed in the space of a few years, Hatch believes, and the addition of the ISO 9002 industry standard for quality assurance only improved things further.

“I was dumped in charge of that but I truly believe that for decade after decade, there was continuous improvement at Young’s,” he states.

Hatch enjoyed many years working for Young’s but during this time, there remained pressure on chairman John Young to sell the valuable site and move the operations elsewhere. Something he fought against time and time again.

“I have wonderful memories of AGMs where John would turn up with a pair of old dusty boxing gloves, something he’d swing around while shouting that ‘I will not be selling this brewery’. Another year he wore a beekeeper’s helmet to keep away the ‘annoying pests’ in the room. Every year there was a different stunt. Fantastic!” he recalls.

But everything must come to an end, and in 2003, Young’s launched a review of its brewing business. Something that culminated in the decision to merge brewing operations with Charles Wells’ brewing operations in 2006, closing the Wandsworth brewery in the process.

“They decided to announce the closure on my birthday. That was a very bad day. I had tickets to see the Queen musical ‘We Will Rock You’ that evening and I remember nothing of it,” says Hatch. “In that summer I’ve never seen so many grown men be reduced to tears. It wasn’t like losing a family because for many, it was losing a family. Young’s took pride in employing families and when we shut, four generations of one particular family were employed there. That was tough.”

Following the announcement, the subsequent months would involve decommissioning the brewery. 300 staff either took early retirement, were relocated or found work elsewhere but regardless, Hatch says the last beer to come out of the brewery was “as good as any” produced during his time there.

Once the dust had settled on the company’s announcement, Hatch and Prentice took things into their own hands. They approached the council to inform them of how much of a loss it would be if brewing was to disappear from the area. They understood but informed the duo there was little they could do.

“We suggested however that if the site was to be redeveloped, the council could force the developer to incorporate a brewing operation into the new setup. This was greeted positively so we were thrilled,” he says. “We knew we couldn’t simply open a new brewery the day after Young’s stopped, so we had to improvise.”

Yeast was added to bottles of wort before fermenting and the yeast skimmed off. And on they went.

“It was a bit underhand, to be honest,” says Hatch. “We weren’t supposed to be thinking about the future of Britain’s oldest brewery rather focused on shutting it down. But that’s that.”

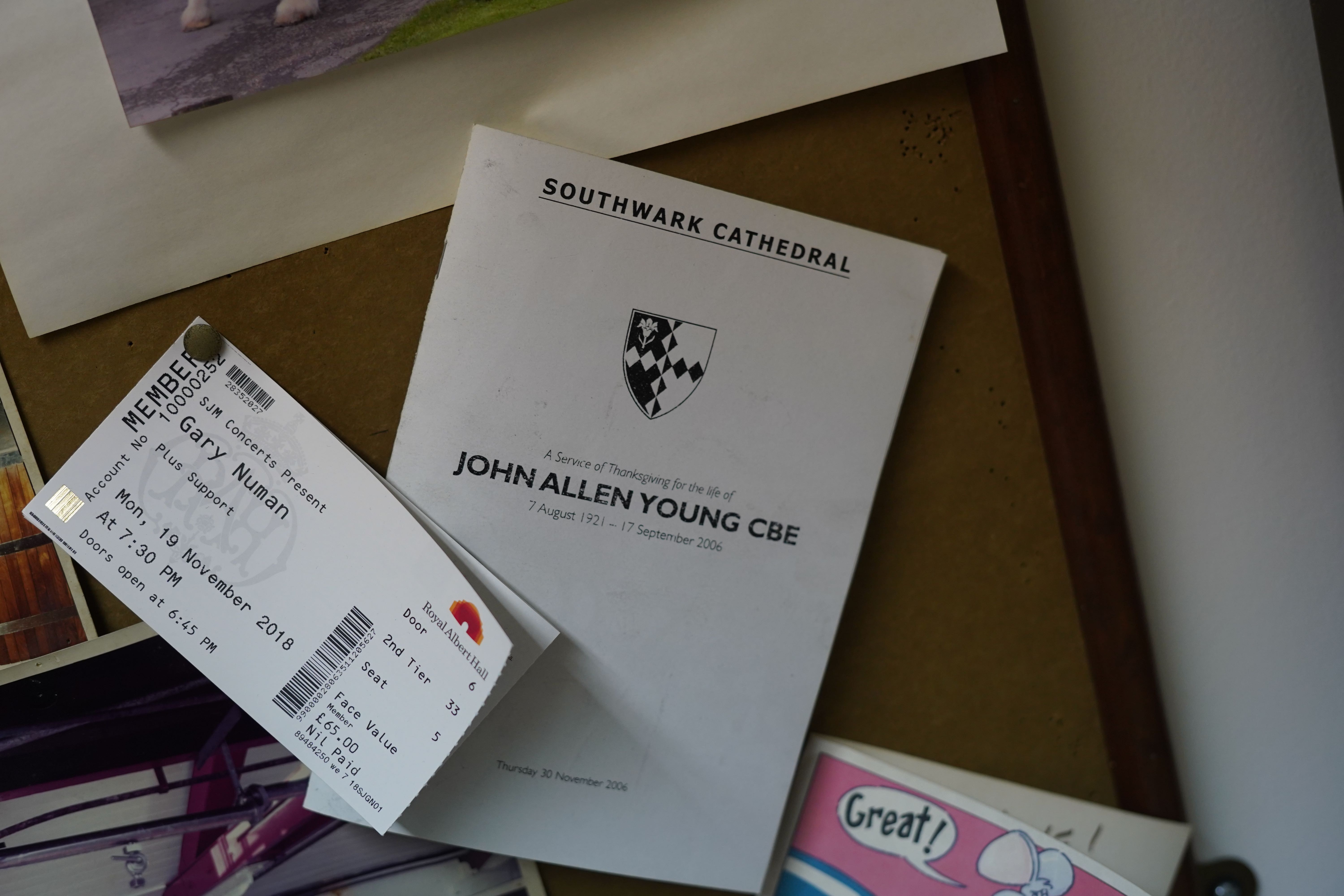

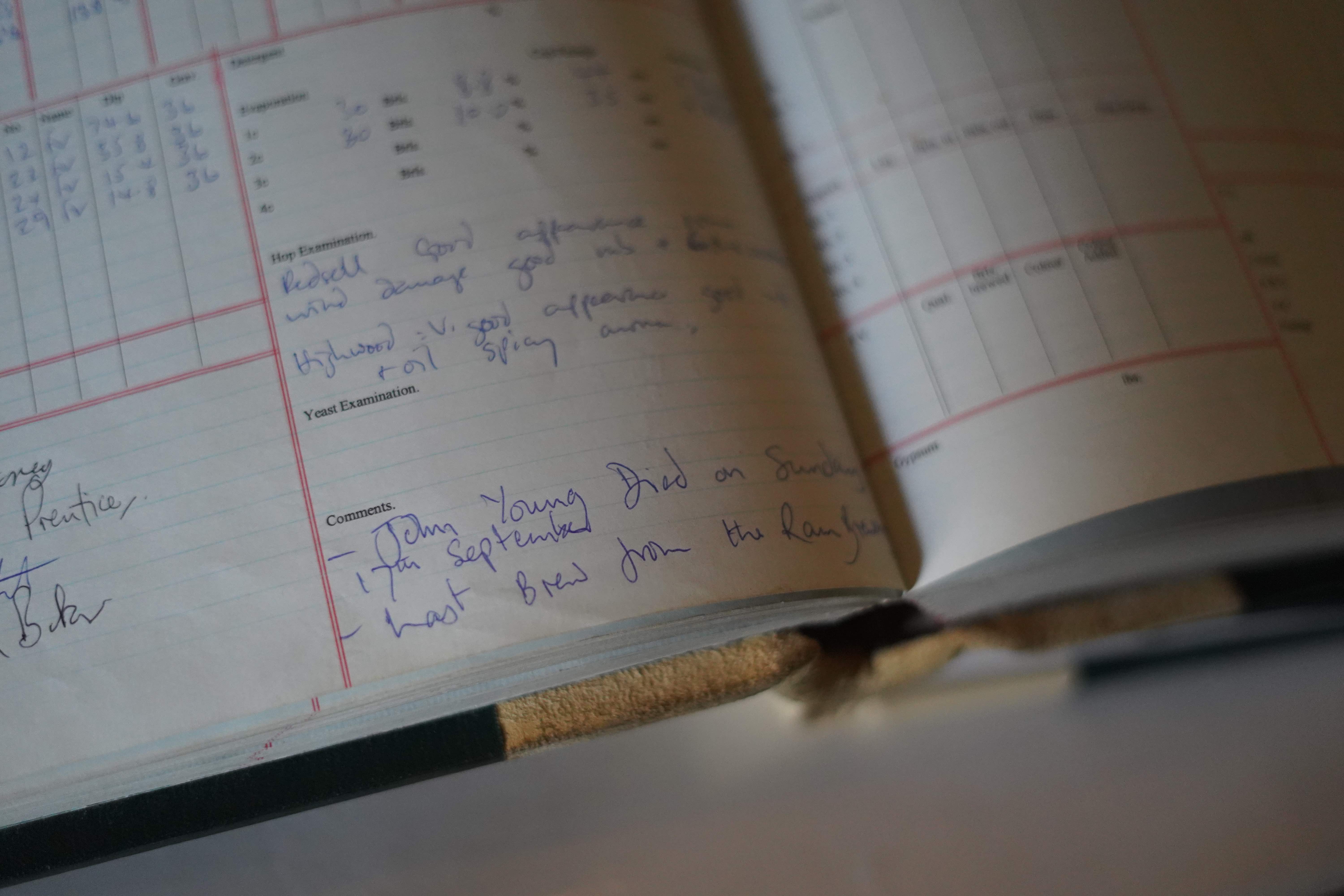

Hatch and the team had a year’s worth of bottles to keep them going once brewing stopped on site. The last brew was completed on the 18th September. The day before, John Young passed away.

Young’s funeral took place less than two weeks later and with it, the first beers from the new operation were somewhat fittingly imbibed. Hatch has many fond memories of his old boss.

“Whilst Young’s were attempting to relocate all of their staff back in 2006, I was offered a job as Health & Safety Advisor for the future Young’s pub company,” recalls Hatch. “Over all my years at Young’s I had taken on a whole host of jobs that nobody else wanted (ISO 9002, BRC Food accreditation, FeMAS, HACCP, CoSHH and finally full blown health and safety). I realised that, on being offered a job in the pub chain, I was going to have to say ‘no’ to Young’s for the first time!

He adds: I felt bad about it so I wrote a letter to John Young explaining that my heart and soul was at Britain’s Oldest Brewery and as such I was sorry but I really could not accept their job. I also took the opportunity to tell “Mr John” what he had meant to me over the years. I thanked him for letting me brew for him and I told him it had been my honour and privilege. Mr Young was already very poorly and I really thought that would be my last chance to express my feelings.

“A few days went by and I had a phone call on site – from John Young! He said he quite understood my decision. I think his exact words were “marvellous! Well done you!”. I told him that Derek Prentice and I were looking at ways to keep the brewing going and he wished us the best of luck. I then went on to promise that I would do all I could to keep brewing on site “while there was breath in my body”.

The maiden beer produced by Hatch and Prentice was a 3.7% number based on the popular Young’s Bitter. But whatever you do, don’t call it by the name it’s also commonly known as, Young’s Ordinary.

“I remember when I was a young brewer I went to use the gents within the director’s block of the brewery. Within seconds, the door slammed. Good grief, I thought, and there was John Young standing next to me.

He barked: “What are you brewing today?”

“Erm, Young’s Bitter, sir.”

He went quiet then replied: “Thank God for that. If you had called it Ordinary I would have fired you on the spot.”

What Hatch hadn’t realised at the time, was that nearby Fuller’s has launched an advertising campaign on double decker London buses with the slogan that read ‘Nothing ordinary about Fuller’s’.

“Poor John saw these adverts pass his office day-in, day-out and after that, we never used the term again!” he recalls.

So despite Young’s ceasing its brewing operations, Hatch and Prentice ensured that beer continued to be fermented on site, and enjoyed on site, too. But plans for another brewery remained unclear. Prentice had been offered, and accepted, the role of brewhouse manager at Fuller’s, while Hatch took on the role of site manager by the site developers. During this time, the stock of bottles and other supplies began to dwindle.

“I was very worried at that point,” remembers Hatch. “So I took myself to King George’s Park in Wandsworth and to an oak tree planted in memory of John Young. There I was, in the pouring rain, apologising to John for failing and admitting that brewing was going to come to an and.”

But it was there and then, that Hatch had his lightbulb moment. To build a ‘Scrapheap Challenge’ microbrewery and brew beer once more. So he scuttled back to the brewery site to announce his grand plans.

He recalls: “I was greeted by a team of 17 depressed staff decommissioning and destroying the brewery. While not strictly in charge, I had a white coat and declared: ‘Hey guys, we’re going build a brewery!’. They were confused and excited, and rightfully so.

“They wanted to know what we’d use and my smart idea of using the scrap metal that surrounded us was immediately dashed as they reminded me, it simply didn’t belong to us anymore. So I went to Young’s CEO Steve Goodyear, thanked him for seeing me and informed him of my plans.”

Hatch had to come clean about the undercover bottling operation that had been taking place in the year since Young’s closed its brewing operations, and also his desires to build a new setup.

“He was surprised and shocked. But he understood. I had permission to use the scrap metal but one thing was clear, that we could not sell anything we make. Fair enough, I thought.”

So once more, Hatch returned to Wandsworth with the good news and was greeted with overjoyed carpenters, welders, electricians, labourers and plumbers.

The diligent bunch set about finding what they could in order to create their new brewery. But when kit such a £3,000 valve was reported “missing”, it conveniently returned unharmed the following day.

“The team would tell the decommissioning firm that any kit moved was the work of the ghost of John Young, and that happens all the time. Thankfully everyone saw the funny side,” he remembers.

The nano brewery that would take the Wandsworth site on the next stage of its brewing journey was constructed in nine days. Many of the former brewing staff returned to christen it, to mixed results.

“You have the phrase too many cooks spoil the broth. Well I can tell you that too many brewers can wreck a beer,” laughs Hatch. “Although we decided on a 4.6% beer, it ended up at half that. It was quite frankly, disgusting. It was oily, rubbery and revolting.”

He adds: “We filmed the entire process down to pouring the first pint and a gentleman called Terry Wilkins, who was a fantastic welder, was the first to the pumps. He couldn’t wait and there he was, lifting the glass to his lips. He made eye contact with the camera and before Terry even took a sip, he raced off sideways out of shot and threw it all away.”

Not one to be defeated, Hatch spent many weeks playing around with different recipes and ideas, with the question of ‘Well, is it beer-like?’ asked many, many times by those involved. But it’s easy to track when the quality and consistency of the beer took an upward turn.

“I remember being paid a visit by an old colleague. ‘Wow,’ they said. ‘That yucca plant is still doing well.’ I’ll be honest, I completely forgot it was there and I sure hadn’t been watering it. But he was right, it was doing great!” says Hatch. But as my beers improved, the plant’s health deteriorated. It was soon apparent that many beers has been poured into that plant over the months. They kept it going.”

The beers Hatch produced evolved, just as the plans for the former brewery site. As potential suitors eyed up the land, Hatch was tasked with providing would-be buyers with tours. On one such occasion, this involved liaising with Mark Cherry, then of UK-based company property developer Minerva.

Not one to ignore such an opportunity, Hatch regaled Cherry with his brewing ideals and the plans he had.

“Of all the interested parties, Mark was the one that showed a real interest in brewing. He found it fascinating and was interested in my future,” he says. “I told him I wanted to stay in brewing, that it was in my blood. Thankfully they won the contract and he knew of my plans to keep brewing on that site.”

Before long, they were clubbing together to buy the ingredients and chemicals required for the ongoing operation. Hatch would brew alongside his salaried activities on site but the costs soon started to add up. It was time for brewing from the Wandsworth site to play a role in the community once again.

“We started with an honesty box in the sample room and collected a few coppers. Small steps!” he recalls. “But soon enough Minerva were approached by a local running group known as the the London Hash House Harriers. They refer to themselves as a drinking club with a running problem, and they asked if they could tour the brewery.”

He adds: “They missed the chance when Young’s was in operation but we arranged it for them. I agreed to brew a bespoke beer on the proviso they’d furnish the honesty box. Something they did with many notes! And that was it, the way forward was tours, comedy nights and similar events to subsidise my brewing.”

Although the site was soon liberated of all its existing brewing equipment, it took on yet another purpose. As a studio for film and television. For eight years, shows such as Luther and Silent Witness leaned heavily on the site, while feature films also called on the gritty, industrial environs.

“I’d often do beers for the crew and they loved the idea. Then they’d enquire about coming back to use the site and also if I’d do another beer. Gladly!” says Hatch. “We’d have anything from a zombie film to a gangster flick. With buildings as old as 1724 right up to the late eighties, it was no surprise we became so desirable.”

More than 120 productions were filmed there over those eight years. So brewing with the sound of AK47 guns going off outside, or a building being blown up, became the norm. But in 2014, it was announced that Chinese group Greenland had bought the site.

Its first venture in the UK, Greenland took on a site with brewing still very much part of its character. Much of the area has changed beyond recognition with more than 600 homes being built on the old brewery grounds. But a working microbrewery and a brewery exhibition are still very much part of the group’s plans as the housing build nears its end.

Brewing will be a firm part of central Wandsworth once again, just in a different guise.

“I’ve seen the London brewing sector change. When the London Brewing Alliance was founded there was around six members,” says Hatch. “And one of those was Windsor & Eton, which was outside the M25. And now there are more than 100 members. What’s happened is marvellous and staggering.”

The London scene will no doubt grow and develop even further but for Hatch, as long as he’s still brewing then he’s more than happy to play his part.

“Paddy Johnson, co-founder of Windsor & Eton, came on a tour some years ago. He said I was very fortunate, so I asked him why. And he simply told me that I’m able to brew what I want, when I want and without the commercial pressures that most breweries experience. He told me that so many would want to be in my position.

“And you know what? He’s right. I’m the luckiest brewer in London.”