The Fisht Stadium in Sochi, Russia.

It’s 10:45pm, 15th June, 2018.

It’s the type of humid, sultry night that makes watching sport a challenging affair, let alone playing close to two hours of it.

The clock hits the 88th minute of a scintillating tie between Portugal and Spain, and the former trail 3-2 despite going ahead twice in this Group B, World Cup tie.

But it’s not over. Portugal have a free kick.

Cristiano Ronaldo steps over the ball. Primed. The position isn’t ideal but this is Ronaldo, after all.

Adopting his trademark stance, he paces towards the ball, smashing it and curving it beautifully around the right-hand side of the wall, beating five defenders and one of the world’s best goalkeepers in the process.

The stadium goes wild and the World Cup, it seems, has now officially started. And though it pains them, there’s applause from Spain fans among the tens of thousands in attendance, too. It was a brilliant strike and such quality needs acknowledging.

Rewind several months and fans of Italian club Juventus felt compelled to do similar when the same player put them to the sword with a sumptuous overhead kick during the illustrious European club competition, the Champions League.

But despite his successes and ability, Ronaldo still has his detractors. Sure, you might not support the teams he plays for, but football is the beautiful game, right? So once in a while, why not enjoy these players for what they are. Does it matter if Lionel Messi is the world’s best and Ronaldo is second. Or vice versa? To be able to watch both is a joy and after all, it’s only football…

And from speaking to Paul Jones, co-founder and owner of Manchester-based Cloudwater, you get the impression he wishes that all of the unnecessary noise and hype around beer could disappear once in a while, so people could enjoy a great beer for what it is, a great beer. Without all of the background nonsense.

The brewery has enjoyed a meteoric rise in less than four years. It has many fans that enjoy the beers it produces but like any successful individual, outfit or business, it has those that for whatever reason, look upon it less favourably.

And for that reason, Jones wants to set the record straight.

“When we started putting together this company in 2014, we had a list of dreams and ambitions. Above all, we wanted to build a great business and make impressive beer that people would enjoy,” he tells us. “We asked ourselves how we could create a company that makes enough money to retire older staff with a good pension. I also had goals such as being invited to the Mikkeller Beer Celebration in Copenhagen and collaborate with breweries we idolise across the globe. So we’re privileged to have hit a lot of our founding goals early on.”

Accolades and awards

Early success is somewhat of an understatement and Cloudwater’s ascension up the respected RateBeer Awards is a fitting way to map the brewery’s rise. In 2016, the business was recognised as the ‘Best New Brewer’ in England. Not bad for a brewery that had only started brewing the year prior. 12 months later, things were getting even more serious. Jones would have needed an additional baggage allowance to haul back 11 accolades from the States, including the fifth best brewery in the world, no less.

But despite such unprecedented success, it was the this year’s awards that really blew his mind.

“Being awarded the fifth best brewery in the world at RateBeer Best 2017 blew my mind. But we reached the end of 2017, and we were pretty sure we’d drop out of the top 10,” says Jones. “It had been a good ride so I listed a number of objectives I wanted to achieve going forward in the near future, and one of those was to hit that number two spot at RateBeer Best, and two weeks later, we did.”

He explains: “There are people that would absolutely ridicule me for saying stuff like that, and they do. But as I’ve said, what we absolutely are trying to be is a brewery that is as involved with its internal processes as it is with the consumer. We really care about our consumers, and that they are excited and satisfied by their experiences they have with, and around, our beer.

“We don’t want to be a band playing to an empty room. We are trying to write music that is so good that we can’t help dancing to it while playing to a crowd that is dancing to it, too. That’s the ambition and I don’t think there is anything shoddy in that.”

In an age where ratings are valued and denounced in equal measure, it’s only natural to acknowledge positive feedback, especially when it can be such a boon to one’s business. Look at Ronaldo. Love him or hate him, you are sure as hell going to find his goalscoring prowess more enjoyable when it’s for your team, not against them.

“It’s weird to find it difficult to appreciate and value feedback, which can be especially helpful if it is included in your internal conversations about quality, value, and more. From my view, ignoring customer feedback is a flawed approach. Sure, we’re in the manufacturing sector but we are moving rapidly towards also being a service industry, so that means customer satisfaction has to register somewhere,” he says. “This is especially valid in the UK, which I would argue is the most competitive beer marketplace in the world. Ratings can make a big impact on whether you can easily shift your beer or not.”

And Cloudwater is shifting its beers. A lot of them. Several new beers are released each week. Whether its a 2.9% Small India Pale Lager brewed with Citra, or an 8.5% Double IPA that comprises Citra BBC backed up by Mosaic and an aroma hop bill of Citra BBC, Mosaic BBC, Enigma and Loral. Their beers are flying out.

London calling

London was, and remains, its largest market. Figures that unsurprisingly impacted its decision to open its first taproom and storage facility outside of Manchester. And if that goes to plan, there could even be another such outpost on the horizon, for the capital, too.

He explains: “Look, Manchester’s city centre population is about 250,000, and the Greater Manchester population is around two and a half million. So out of that, how many come to the centre to drink beer. And of those, how many of those like our type of beer?

“Sure, the scene here continues to develop, slowly, but there hasn’t been the growth in craft outlets to match the number of breweries opening. In London, the demand and market are massive and it makes sense to put your beer where the people are. Especially when they’re the type of people that already enjoy your beer.”

Jones is hopeful that between 10-12% of everything the brewery packages in Manchester each week will go through the new facility, which is located on Enid Street in Bermondsey, a town in the London Borough of Southwark. When it opens, it’ll be in good company a couple of doors down from Brew By Numbers and also Bristol’s Moor Beer, which also opted for the area for its capital site. In addition, breweries such as The Kernel, Fourpure, London Beer Factory and Anspach and Hobday call Bermondsey home, as does distributor The Bottle Shop.

“London gives us an opportunity to close the gap between the consumer and us, and gives us a direct opportunity to convey what we’re about, our vision, and ideas,” he says. “But these new premises have to work financially, too. We don’t have cash to burn and we’re not doing this off the back of any kind of refinancing because we’re trying to make this work out of the company’s own pockets as much as we possibly can.”

He adds: “We’re trying to progress slow and steady and to ensure any new taprooms operate as a going concern. If we chose a quieter neighbourhood and the outlet had a flat six months, that would drive our attention and resources away from the brewery, and the focus on beer quality, to how we could make that work. They need to be as self-sufficient as possible from day one. The whole company is better off if we focus on getting new retail sites off the ground without keeping any of us awake at night.”

Being kept awake at night is something Jones knows all too well and he references the design misstep that put a grey cloud over the brewery at the beginning of this year. Collaborating with Miami’s J. Wakefield Brewing brought the branding of the US brewery’s beers such as ‘Orange Dreamsicle’ into laser focus in the UK. Labels that placed scantily-clad women at the fore of design. With such feedback taken on board, the collaboration between the Miami and Manchester breweries attempted to indulge in some self-deprecation.

The branding of the beer, ‘Shelf Turds’ featured illustrations of Jones and Jonathan Wakefield in their underwear. However, the market disapproved. Not only was the beer removed, but Jones took it upon himself to liaise with J. Wakefield and encourage them to look again at some of their existing branding, which they rebranded in turn.

Despite being commended for the lengths he went to, Jones still feels regret over the situation, but would also like a wider industry dialogue on the nuances of such instances, too.

“It was very tough, and extremely stressful. Even though I might have done a thousand positive things for the industry up to that point, nothing else seemed to matter, one mistake and that was it. I was fucked for a month, if not longer. And irrational fears of another Twitter storm still lingers on.” he says. “It felt like people threw anything positive we had done out of the window for that one mistake. We have high standards for ourselves, and we don’t want to misrepresent our values, or offend anyone, ever. Maybe we’ll move past this being brought up in every interview eventually, and I hope we do, but the way things manifest themselves online at the moment an element of point scoring and powerplay is the norm.”

Online opinions

Jones goes on: “I say to my guys all the time, because we get a lot of stick from a lot of people, that it’s either people trying to slow us down or exert some sort of influence over us. It’s rarely a truly altruistic concern that someone has when they flame you online, it’s really that they want to be powerful, and to be this week’s judge and jury.

“What seems to be getting lost behind some of the most seething outrage is a call in and focus making the online spaces around beer a more positive. If I was a wine drinker right now and I tuned into beer Twitter at the wrong time, as this week’s spat or argument aired in public, I might be put off quite quickly and think ‘Wow this is awful!’.

“I guess it’s quite normal that overwhelming positivity and good gets lost against the negative, and I feel that there’s, at times, a lesser overview than there could be of how the industry really influences the world. I think that’s a big problem but, you know, online platforms don’t really make long form, nuanced conversation easy, or in some cases, possible.”

Jones feels that the J.Wakefield incident only started to die down after weeks of criticism and it was something that he says nearly made him pull back from being the public figure he’s known as in the industry.

“It made me feel as if having a public voice, and raising issues outside of beer production wasn’t worth it. Because if what is going to come of me having a voice is being shot down so easily, then it just doesn’t feel worth it. I almost decided I won’t have a voice and we as a brewery will speak on things less. I’ve tried to demonstrate that we can just be humans, a company of humans with values, but at least at this point in time, it feels there is no margin for error,” he explains. “I worry about how many voices are silenced right now. There are people in the industry that have things they would love to express but I know that there are many that are terrified about putting their values out there because as soon as you do you are pinned to a mast, and held up to impossible standards. It’s no wonder the vast majority of breweries just stick to beer, and conduct themselves in a bit of a social or political vacuum – it’s far less traumatic.”

He adds: “I know I now find it ever more difficult to make statements based on my experiences, without second guessing if people will call me out for something that’s visible from their point of view but maybe not mine. But I’m more concerned with trying to demonstrate that people can trust us, and that we’re doing our best to offer them long-lasting value in our beer. That’s what’s crucially important.

“I’m very hard on our beer quality so I make sure to exert every little angle of scrutiny over what is flawed in every batch, with a view to protecting the consumers experience. Nothing else pays our bills, keeps our lights on and makes the other positive things we want to do outside production without customer satisfaction.

“So it is important to me that when someone is disappointed with their experience we pay attention. Reacting to negative feedback as if it’s just a consumer complaining is too narrow. Sometimes customers think we’re so good that they’re deeply upset to discover we don’t always hit our mark, however hard we try. It’s important to me to come off the back of even angry complaints asking myself what we can do to make things better?”

Jones is acutely aware of the positive impact strong ratings and accolades have had on his business during these first three and a half years. But in the words of Uncle Ben from the Spiderman comic book universe, ‘With great power comes great responsibility’ and that’s something that no doubts resonates with the Cloudwater director.

“If we carry out any critical evaluation of our beer in-house and we flag something up, and if a customer picks up on that too, then we escalate that issue to rectify any problems as soon as we can. As long as the feedback is genuine, of course. I have always tried to take any negativity thrown at us from the most positive angle I can, and to use it for good. I have more than enough on my plate looking after the business, team, and customers that want us to succeed than to be slowed down by people hoping we’ll fail,” he explains. “I would like to promote more appreciation of the stuff that will build the industry into the right space rather than what will chip away at it. Because we’re only really good at doing the latter right now.”

Jones adds: “As food and drink has become a consumer-facing, direct communicating industry, I see a lot of animosity, of businesses being negatively impacted by shabby reviews and how it drags them down.

“Some reviews are genuine and some are not, and it can be difficult to separate to two sometimes. We’re all doing our best and it’s easy for consumers to expect utter flawlessness in every little thing but that’s not always possible, despite every effort. It’s made especially tough when we’re working at the scale of how businesses such as ours operate.

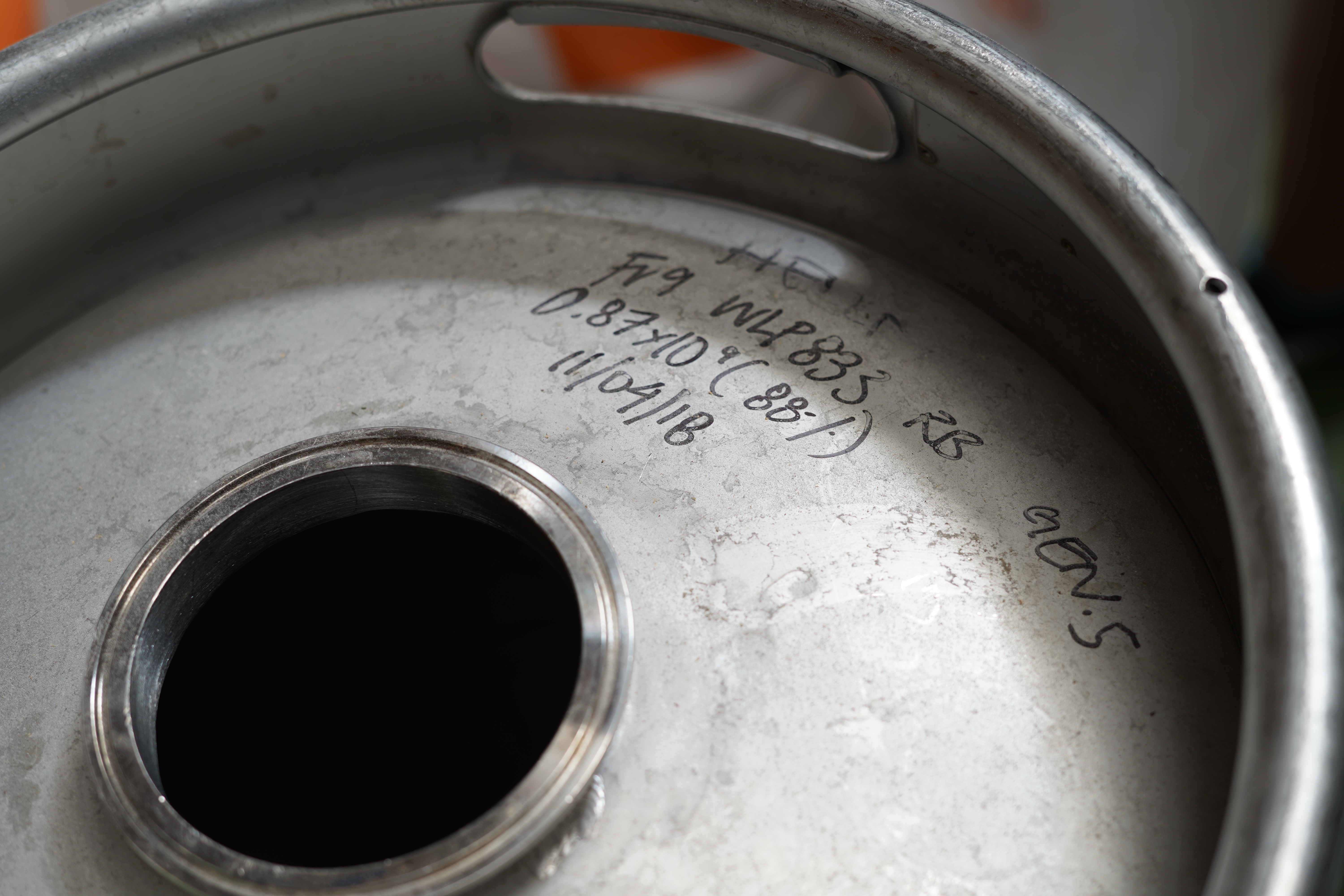

“We make beer in small batches, with ½-3 brews per release. We’re not blending 5, 10, 15 batches into a single tank where we can correct any errors in the early ones with recipe or process changes in the latter ones.

“Unblended beer is what most smaller brewers make and there is a margin for error there that doesn’t exist in macro blended beer. So it’s a question of asking how do we keep raising expectations, telling folk it’s a better experience than what they can get elsewhere, while also not building a perception that we can be utterly flawless.”

Quality first

One approach Cloudwater has taken to quality is through the adoption of how it conveys freshness information on its canned output. The business has printed packaged on dates since September 2015. Jones has previously said that the business has compromised reasonable shelf lives with short BBE dates, so to encourage every link in the distribution chain to move its beer in the quickest possible fashion.

Such an attitude has helped ensure there aren’t stockpiles of its beer anywhere, except for the days after a packaging run, when a few pallets of cans sit in near suspended animation conditions in their 4ºC cold store.

As the industry and its distribution model develops, the brewery has gone on to adopt a new model and that’s the addition of a ‘Freshest Flavour Before’ date. This is the brewery’s method of saying that provided the can has been well looked after once it left our warehouse, it should present very well to the consumer, and as was intended, before such date passes.

After the FFB date, the beer should still be of high quality, but it will have lost some of its freshest edges, and will no longer be quite the same beer that was passed in the brewery’s sensory panel for packaging. The BBE date conveys when we expect the beer to start a “less graceful decline” towards being a shadow of its former self, by starting to showing age related off flavours.

The inclusion of such information is the latest addition to the product breakdown featured on each of its cans. But since its initiation, the brewery has always featured a comprehensive list of product ingredients on its labels. Something that has developed further to promote hopping rates and similar details. It’s a positive step for the consumer, and Jones believes it’s an effective way to educate the drinker. Despite the possible detriment it could have on the wider brewery at large.

“I took that decision at the start to put every ingredient on our beers. Did I make it easier for other breweries to learn how we are putting those styles together? Absolutely, we made competition more intense for ourselves, but hopefully made life better for our consumers! I think given that we’ve not seen a wide adoption of ingredient publishing, it goes to show that many breweries are still reluctant to share their ingredient intellectual property, and I can understand why,” he explains. “Go back to 2015 and it might have taken six months for an alternative style to see the light of day. Now, you can put out a beer and it’s maybe a month before a bunch of alternatives hit the market.”

He adds: “There is an intense geographical overlap of breweries reach here in the UK, and to build a sustainable future, you have to ask yourself how you can figure out if there are any protected spaces outside of tied tap handles. I feel as if we have functioned as an R&D brewery for the rest of the UK sometimes. We have taken a lot of risks, and sure we have benefited in taking those risks as well, but in today’s fast paced environment, things change all the time.

“It’s not that long ago that we started canning in 440ml cans, and a little bit further back when we introduced the regular Double IPA releases. Now both are commonplace, you can’t move for them. The same is starting to apply to DDH (Double dry-hopped) beers. For us that means literally double the quantity of hops, not that we dry hop the beer twice. I wish there was a term that meant the same thing for every single brewery. Instead, it can often feel like a marketing term rather than something to be transparent over.”

With that in mind, Jones admits that it could become harder and harder to maintain a commercial will to offer up such transparency going forward.

“I truly hope it doesn’t end up being the case, but when you look at how far things have come, and how much thing have changed in the last two years, then you ask yourself how much could happen in the next two, you find yourself asking whether being as open as possible will negatively impact us as a business. I hope not. And I want to be as transparent as we are today long into the future,” he laments.

The cash conundrum

Jones is proud to be part of the brewing scene in the UK. He’s often said he is privileged to be part of the burgeoning modern Manchester beer sector but equally, that Cloudwater is not a dyed in the wool Manchester brewery. He takes inspiration from London, Leeds, Bristol, the lot. And he’s a big fan of North America. Many seeds will have been sown on his visits overseas, ideas that would be transplanted to the UK audience weeks, months and years later. One such goal, so ably achieved by many US breweries, is the ability to drive the self retail model.

“We are constantly waiting for hundreds of thousands of pounds that’s on our books, revenue that’s hopefully coming back from our customers. Most of them do their level best in their own way, but there is always an obscene amount overdue on our credit terms, and that’s money I can’t use to build my business, to invest in staff and training to make higher quality beer,” he says, cutting a frustrated figure. “Cash flow issues do not escape a brewery like us at all, and are depressingly prevalent from the top to the bottom of the chain. So if we were able to drive more self retail, it would help us achieve increased financial comfort that we still don’t have, and it would allow us to make better decisions for our consumers.”

He adds: “We want to develop our online store, and want to develop what people can buy from us from the brewery and the taprooms. Each time I visit the US, I am astounded by the commercial realities that don’t ever feel like they could be a possibility here in the UK. I can visit a brewery that finds that there is nobody else that makes their style of beer for hundreds of miles, or even no other brewery that makes modern beer of such quality for hundreds of miles. Some breweries can develop great direct retail support, gaining amazing loyalty and a host of benefits that come from being somewhat stylistically or geographically isolated.

“That is a massive part that has made the US stand out and grow, and it’s something we don’t have a cat in hell’s chance of doing in the UK. The taps that we hope to pour through here are the same taps that our peers want to get on, and for anybody that debuts a new style in the UK these days, you can bet your bottom dollar they’ll be many similar versions in a month or two, which is potentially great for the consumer, but it puts us in a very different position in the UK than our peers in the US.

“I’m good friends with folk in the US that have queues of hundreds of people out the door each day. You could never imagine that same situation unfolding over here because we are brought up on pub culture. Buying beer, and enjoying it in a pleasant environment is the norm in the UK. So when we have an online shop platform that gives us reach geographically, or that meets the needs of those customers that require such convenience, we need to protect our customer’s experience and do our level best to make online sales work as perfectly as a trip to the local pub.”

Development to its online platform continues, as does its upcoming London taproom and a new unit adjacent to its Manchester brewery. The Manchester facility will house a cold store allowing for direct can and bottle sales, storage, and a taproom with purpose-built bar, seating, amenities and events space. It’s an impressive setup that will no doubt prove a go-to spot upon opening this summer.

Jones continues the investment in its current brewery site despite the lingering prospect of the need to move facilities in the future. It’s existing lease doesn’t expire for a few years, something that is likely to be extended. It’s something that remains at the back of his mind, but he knows that the only way to prepare for such an eventuality is ensure the business becomes as profitable as possible before then so to cater for the high costs of a move.

“We are still definitely going to have to find a new home in the not too distant future and we’re going to need to be able to afford to move. It’s going to cost millions of pounds to do that and to be able to setup a new site and get that ready before we move over is likely to drain all the profit we’ve made up until then many times over. It’s not going to be an easy thing to manage and I’d like to think we can get someone on board to head up that side of things,” he explains.

At this point in time, Cloudwater employ 21 people on site at the brewery, which include three in work production, three in cellaring and thee in packaging. Recent staff hours have been cut to 40 hours per week while the wage bill has increased 23%.

Jones is also working on raising the minimum wage for each member of the team at the brewery to £30,000 per annum. The company has also just employed Doreen Joy Barber, formerly of Five Points Brewing Company in London, and Jeremy Stull, a founding member of Manchester’s Beermoth.

Stull will take ownership of managing the brewery’s barrel-aged output, a part of the business Jones admits has sat on the back-burner somewhat while its focus on fresh beer grows apace. But to be firing on both cylinders with both, is one way Jones believes the brewery can sustain growth in what is becoming an increasingly challenging and competitive UK beer market.

He explains: “I genuinely don’t believe the wider industry can keep going at the pace it is without a bunch of things changing. Traditional beer has waged a covert propaganda campaign against all keg beer, and lager for decades, and that’s impacted the growth opportunities of microbreweries wanting to make modern keg beer in some rural locations, and made another hill to climb for any brewery devoting time to independently brewed lager. It’s tough for them to break into lager because lager has been viewed as a commodity by those that have bought into the CAMRA rhetoric over many years.

“But lager is the biggest market in the UK and it would be nice if we could all get a little piece of that massive pie, reaching new customers and helping bring them into a world of new beer experiences, as it presents such huge growth opportunities for everybody.”

Maturing marketplace

Opening up good beer to the wide market is why Jones has great admiration for businesses such as BrewDog, which he feels are effective at converting macro drinkers through its bar portfolio.

“I’m convinced that we are one of the most competitive marketplaces in the world and there is 100% geographical overlap for all but the smallest breweries across the UK. A tap in Manchester might be pouring us tomorrow but not the next day. So we have to wait our turn to go back on,” he explains. “We’re limited by the number of speciality outlets that exist to pour great beer. Breweries like BrewDog help increase our potential customer base by showing people new to craft beer what exists beyond the macro beer world they may be used to. And they should be celebrated for it. Without such efforts, our market would grow at a much smaller pace.”

And Jones wants to do his level best to affect that change. He just doesn’t expect an easy ride doing it.

And Jones wants to do his level best to affect that change. He just doesn’t expect an easy ride doing it.

“Broadly speaking, people think we’ve somehow had a lot of luck and that things have been straightforward for us on the pathway to whatever semblance of success we enjoy now. I can’t tell you the number of people that I’ve spoken to in the industry and the number of consumers that approach us with the impression we’ve had it easy,” Jones stresses. “I’ve invested in travelling and spreading the word of modern British beer, and that doesn’t only benefit Cloudwater. If you spend time elsewhere in the world talking about the positive achievements of modern British beer, and developing the perception of British beer, it benefits everyone.

He adds: “We’re sometimes held up to impossible standards and have all sorts of accusations thrown at us. But I can’t stress how tough it has been to come this far, and how tough the future looks. There’s no silver lining on the horizon yet. It’s difficult to appreciate the stresses and work that go into any success in the industry, without being on the ground to see it first hand. I’ve spent time with folk that sell literally hundreds more stock items from their front door than we ever could, and I might have initially held a narrow-minded impression of their lives being somewhat easy. But having seen the effort that goes in from dusk till dawn, it gave me a real insight otherwise.

“If everyone is working really hard why does hard work not equal the same success for everyone? It’s possible to think it must be down to luck. But it’s not the application of effort alone that achieves results. It is focus, and having vision, taking risks, being bold, and then trying your goddamn best to follow it up with something even more meaningful next time.

“And hoping it works.”