In his latest article, Tim O’Rourke takes an in-depth look at some of the ancient brewing methods still taking place across Africa.

The process of traditional African brewing has been passed down by word of mouth through generations. Some of the equipment may have changed but the basic scientific principles of fermentation and mash conversion still hold true.

Beers are made from locally grown cereals like sorghum, millet, rice, and maize which all have gelatinisation temperatures higher than malt (range 75 – 95C) which are above the deactivation temperature of malt starch hydrolysing enzymes.

This requires separate cooking and gelatinisation of the starch before cooling to allow the enzymes to break the starch down to fermentable sugars.

All the traditional brewers are faced with the same technical problem and each African country has developed their own solutions. Below we will describe quite different methods to produce beer in East & West Africa.

Production of Ajon in Kampala, Uganda

Visiting a traditional Ajon Brewery involved a meeting with Deo Lule, the head brewer of Uganda Breweries in Kampala.

Ajon splits mashing into two parts with the different grists being mixed together in the fermentation vessel. By splitting mash conversion, the brewer can achieve all the required operations of mashing without needing an accurate thermometer.

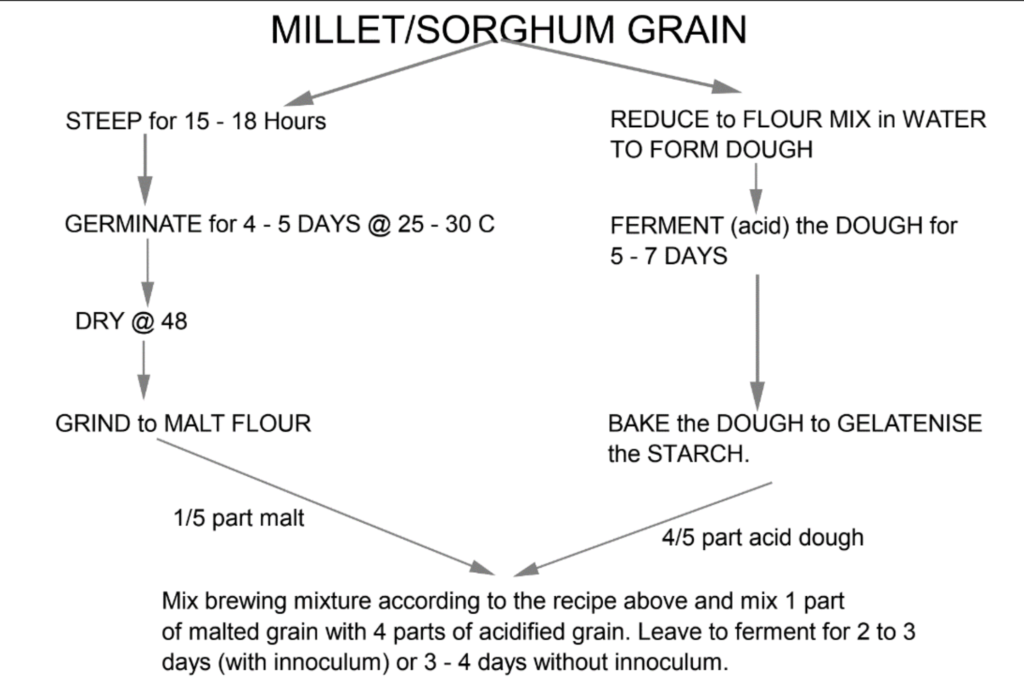

The process involves:

- Burying ground damp sorghum in the soil to encourage the growth of lactic acid bacteria which acidifies the grain.

- After a week the acidified grain is dug up and baked on an open tray to gelatenised the starch granules rendering them accessible to enzymic attack. Acidification drops the pH in the fermenter to less than 5.0 which is suitable for the amylolytic enzymes.

- A separate portion of the grain is malted in the conventional way to produce sprouted sorghum which is sun dried and milled and provides the source of starch hydrolysing enzymes.

The brewer thoroughly mixes 4 parts of the ground acidified cooked grain with 1 part of the malt at a ratio of 2.5 litres of water to 1 kg grist and is transferred to a plastic barrel (a repurposed 200 litre plastic drum) for fermentation. The volume is made up to the equivalent of 7 litres of water to 1 kg grist.

The wort is fermented in recycled plastic detergent drums and wet sacks are attached to promote cooling. Typical fermentations take around two days. During fermentation the enzymes break the starch to sugars allowing the bacteria and wild yeast from the malted grain and environment to ferment the wort producing a low alcohol beer.

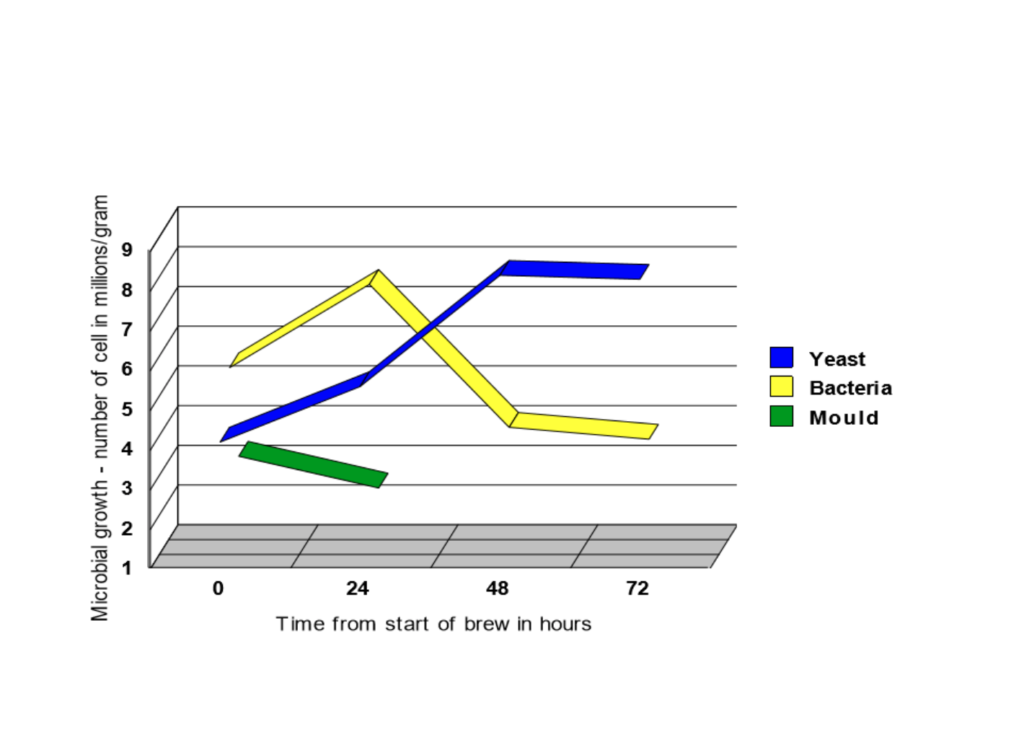

Fermentation is carried out by a mixed population of micro-organisms whose activity is largely controlled by the fall in pH. Moulds only making a brief appearance at the start and is followed by the growth of lactic acid bacteria. Bacterial growth falls away as the pH continues to drop allowing the yeasts to flourish (particularly ale yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae sp.) and produce the alcohol.

Ajon Production

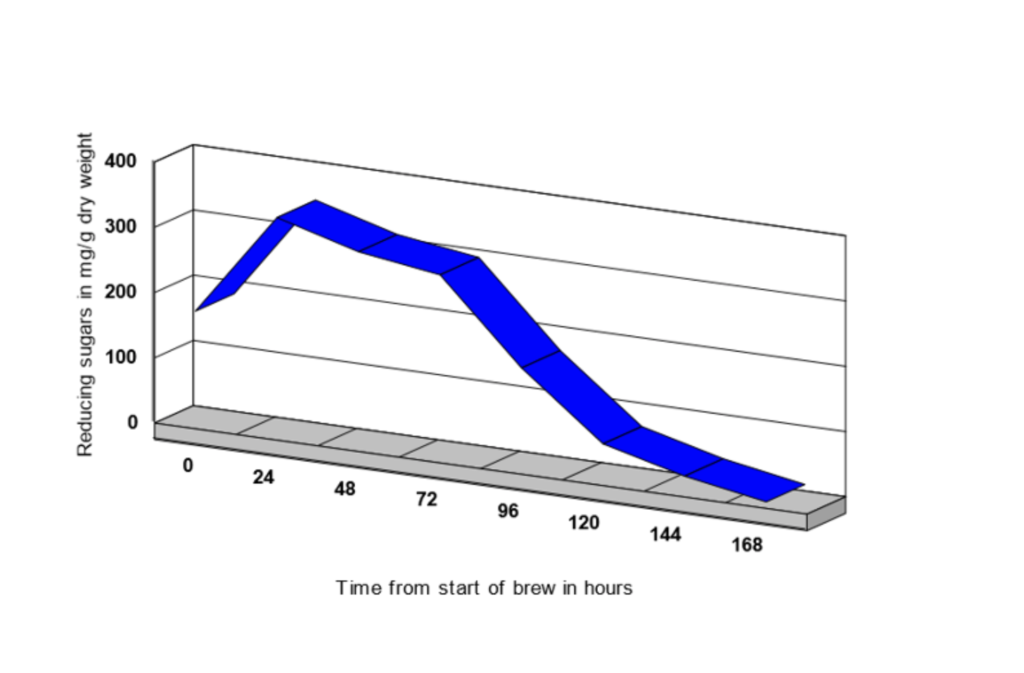

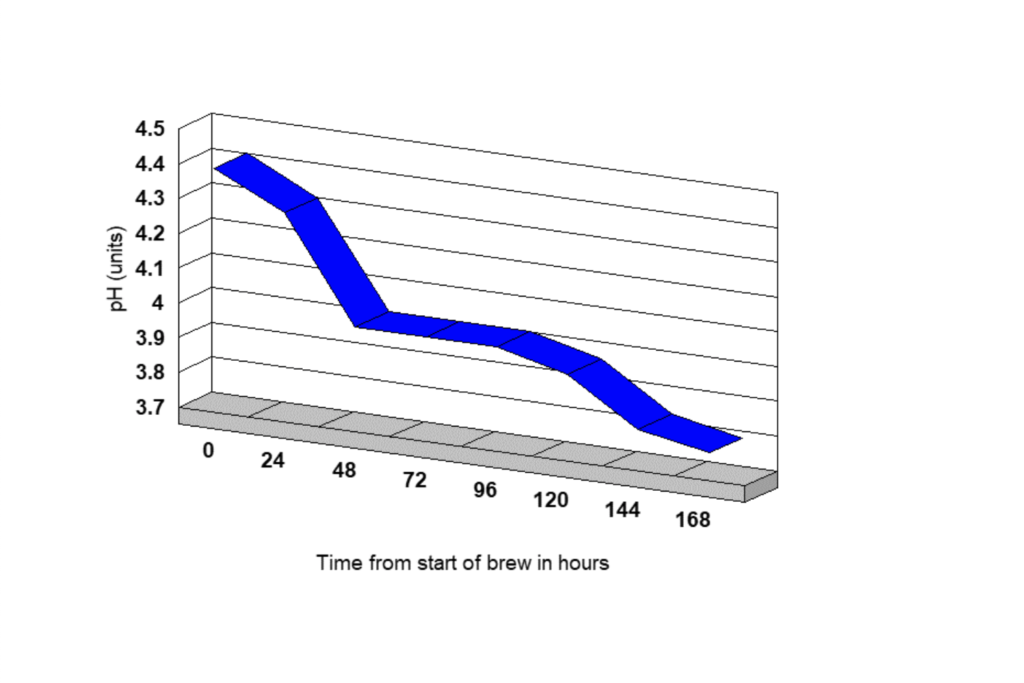

Fall in pH during fermentation. The initial pH is lower than a normal brew because of the addition of the sour grains and continues to fall following the growth of lactic acid bacteria resulting in a lower final pH giving the beer a tart acidic/metallic flavour.

Microbial growth in a traditional fermentation. There is a rapid increase in acidity, which will halt am-ylase activity after the first 24 hours. The yeast fermentation then takes over to produce ethanol.

Production of Mbege in Moshi

With the help of Matthew Manyaga and members of the team from Diageo Kenya and During a visit to the country, visits to a sorghum maltings (steeping shown on the left) and a brewery in Moshi took place.

In Tanzania plantain (bananas) are commonly used as an adjunct to produce a fruitier beer. Traditionally beers were bittered with quinine, but at this time the practice had ceased, as it was considered a health risk.

Plantains are mashed and allowed to stand overnight where the banana juice concentrate acidifies, the extract is then squeezed out as shown below. This is mixed with a boiled malted sorghum mash to give the required acidity needed for mash conversion and fermentation. A handful of ground malted sorghum is added to the fermenter to supply the necessary enzymes.

The rest of the brewing and fermentation process is similar to that described for Ajon. The beer produced is quite thick and is usually drunk from cups which are consumed in the adjacent bar.

Production of Bili Bili in N’Djamena (Chad)

Accompanied by Miaro Rismalo and my brewing students we visited a Bili Bili brewery in the suburbs of N’Djamena in Chad which uses sorghum and occasionally rice to brew beer. Chad is one of the poorest countries in Africa and the affordability of the beer is important. Brewing Bili Bili is complicated and involves a series of mashing and filtration stages to produce the wort for fermentation.

Ground Malted sorghum is mashed with warm water at around 60C, (below the starch gelatinisation temperature) and supernatant is filtered to be stored as a source of malt enzymes. Gumbo (the sap from the Triumfetta tree) is added as a clarification aid.

- The solid part of the mash (I) (remaining grain) is remashed and boiled for two hours to gelatinise the starch and then left to cool for a day.

- The liquid part of the mash (II) is kept separate and will be infected by natural airborne spoilage organisms (lactic acid bacteria) and the pH will fall between 4 – 5.

- Once the mash is cooled the two liquids are combined and left to stand at round 60C to let the enzymes break down the available starch to produce fermentable sugars.

- The wort is allowed to cool to ambient circa 25 to 30 C and is filtered through the basket with a bed of dried grass before being collected for fermentation.

This is similar to European style brewing and produces a relatively bright wort but has been adapted to meet the requirements to gelatinised sorghum.

Yeast & Fermentation

Traditional African beers rely on spontaneous fermentation by “wild yeast”, mixtures of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria. The predominant sugar extracted from the cereal is maltose and the most common yeast strain, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (top cropping Ale Yeast) is particularly well adapted to ferment “wort” and is the most prolific yeast variety found in any mixed culture fermentation.

Brewers go to great lengths to keep their source of yeast safe. For example, Belgium Lambic Brewers preserve their yeast and the microflora by not cleaning around their cooling and fermentation areas to preserve any microbes present and use wooden barrels infused with micro-organisms.

Tropical Brewers use clay pots which are infused with microbes and become a source of inoculating the wort.

Both systems have limited capacity to hold micro-organisms and fermentation may be slower while yeast grow to complete the fermentation. Other breweries practice repitching or “back slopping” by saving yeast from an earlier fermentation often by skimming the foam and adding it to the next vessel to supply enough viable yeast to complete the process.

Examples of how yeast is preserved and transferred between traditional brews:

- In Uganda Ajon relies on microflora in the brewery to inoculate the wort and since the wort is not boiled the sorghum added to the mash is also a source of yeast and bacteria. The malted sorghum is actually referred to as “yeast” by the Brewers.

- In Tanzania the mash for Mbege is boiled with handfuls of raw malt added to the cooled acidified banana juice to provide the microbial inoculum to complete the fermentation.

- In Chad the brewers of Bili Bili use a process of back slopping. Good quality Bili Bili has a good foam present on the drinking vessel and once consumed the foam is collected by the server who uses it to repitch the next brew, perhaps not the most hygienic of processes. This may be necessary since fermentation is now in plastic containers rather than clay pots and can no longer carry the microflora from one brew to another.

Heritage & Beer Drinking

Drinking beer was an important part of early cultures often based on rituals and ceremonies. With the introduction of European style beers many of the ceremonial functions have been stripped away and Traditional Beers have been relegated to the low-cost end of the market offering a more affordable source of alcohol.

Much is made about the ceremonial importance of “drinking through straws” shown in most images and carving of beer drinking in Africa and the Middle East. While this may be an important aspect of the beer drinking in some cultures my observations suggest that drinking through straws was restricted to unfiltered beers such as Ajon to separate the husk residue from the liquid but filtered beers such as Mbege and Bili Bili are drunk directly from a cup or gourd.

In Africa traditional beer amounts to about a third of the total volume of beer produced and is generally consumed by the less well-off citizens. Many working people drink European Beers after they receive their pay and traditional beer (which cost about 1/5 of commercial beers) until the next paycheck. The traditional beer is something of an acquired taste. The cost of a litre of beer in Tanzania is 10c US – around a 1/10 cost of regular lager.

Beer Taste and Quality

Beer quality is important, most traditional beers have a short shelf-life, staying fresh for just a few days. The beer is usually drunk fresh in the brewery. The presence of beer foam is considered to be a good indicator of quality.

Similarities between current practices in Traditional brewing and those captured on early pottery show just how little has changed with the passage of time. It is possible to relate the current brewing practices with those shown in models and friezes many thousands of years old.

The similarities between the ancient and modern brewing practices and beer drinking are striking, making it a good way of appreciating ancient brewing methods which have been passed on by word of mouth and still being practiced today.

While practices remain unaltered over the centuries, new materials such as metal pots and plastic tubs often recovered from larger commercial brewing have replaced many of the more fragile ce-ramic and wooden vessels.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank my local mentors and guides Dea Lule and Okelai John Ariko from Diageo Breweries Uganda, Matthew Manyaga from Diageo Moshi Brewery Tanzania, Luis Tamio Supply Chain Director and Miaro Rismalo Head Brewer Brasserie Castel Chad Brewer-ies as well as all my students in who all supported and accompanied me in the brewery visits and research.

Citations and Further Reading

1) Nicholas P Money “The Rise of Yeast” pub Oxford University Press 2018

2) Matthew A Carrigan “Why do we drink alcohol” presented at British Academy London 2018.

3) Tim O’Rourke “Brewing up the Past” Brewer International Volume 2 Issue 9 2002

4) Michaela Charles, Tasha Marka and Susan Boyle “A sip of Ancient Egyptian Beer part of Pleas-ant vice series”, Blog and video https://www.facebook.com/britishmuseum/videos/ancient-egyptian-beer/754992025293909/

5) Ian Hornsey “Taming the Yeast” Brewer & Distiller International June 2011