How do you build a profitable brewery? Being able to define a customer is a great place to start explains Julian Bourne the CEO of Sellar, a brewery sales platform that helps breweries ship anywhere in the UK so customers can order any product from any brewery.

Being profitable is sexy again. Personally, I never really understood why it went out of fashion. Maybe it’s because companies that grow fast amass media attention and steal all the headlines.

We all read about the success stories. The ones that made it. However cheap capital and chasing growth at all costs resulted in many businesses selling a pound for a penny. It reminds me of the old joke: “we lose money on every sale, but make it up in volume.” ****But can bad unit economics really be fixed with scale?

With margins under attack in the brewing industry, it’s becoming increasingly important to focus on the nitty-gritty detail that drives our business. The numbers and KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) that ultimately determine if we succeed or die. We must be able to answer questions such as:

- How much do we earn (or lose) from every extra customer each year?

- How much does it cost us to acquire that customer?

- What’s the payback period?

- What’s the lifetime value of that customer?

These business fundamentals matter once again.

This series aims to shed some light on how to win at the new game: increasing profitability and maximising margin.

Welcome to post 1 of this series. In this post, we define: “What is a customer?”. An essential starting point in better understanding our unit economics.

Define customer

From thousands of conversations with hundreds of different breweries, I’ve heard a large mix of different definitions when answering the question ‘What is a customer?’.

There’s a huge range of answers from the exceedingly specific (less common) to the excessively general (more common). Some have thought long and hard about each customer category they serve through each channel they operate in. For others, a customer is simply anyone who’s ever bought a product from them.

It’s an area we’ve been doing a lot of thinking about at Sellar HQ, especially in the lead-up to our decision to base our pricing model around the number of customers a brewery is working with.

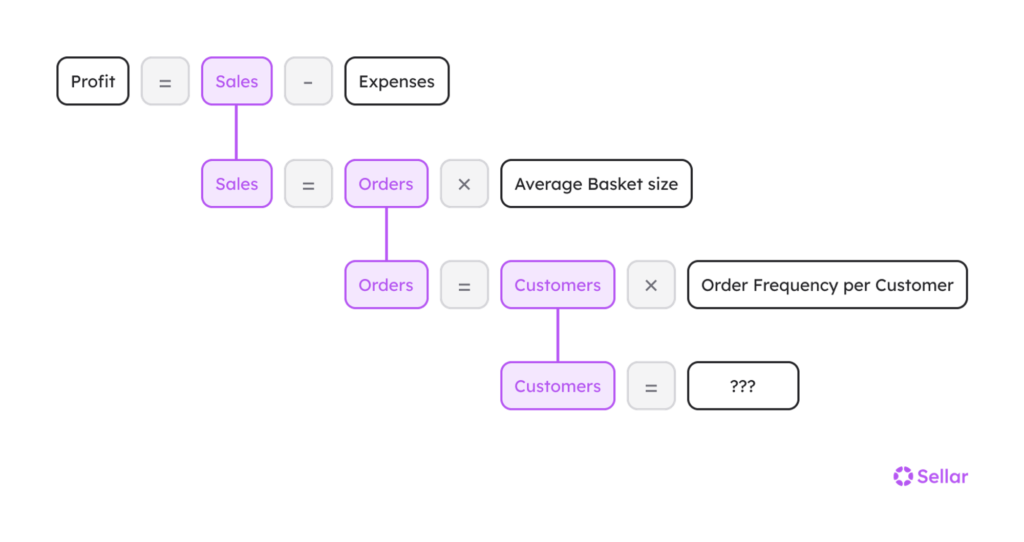

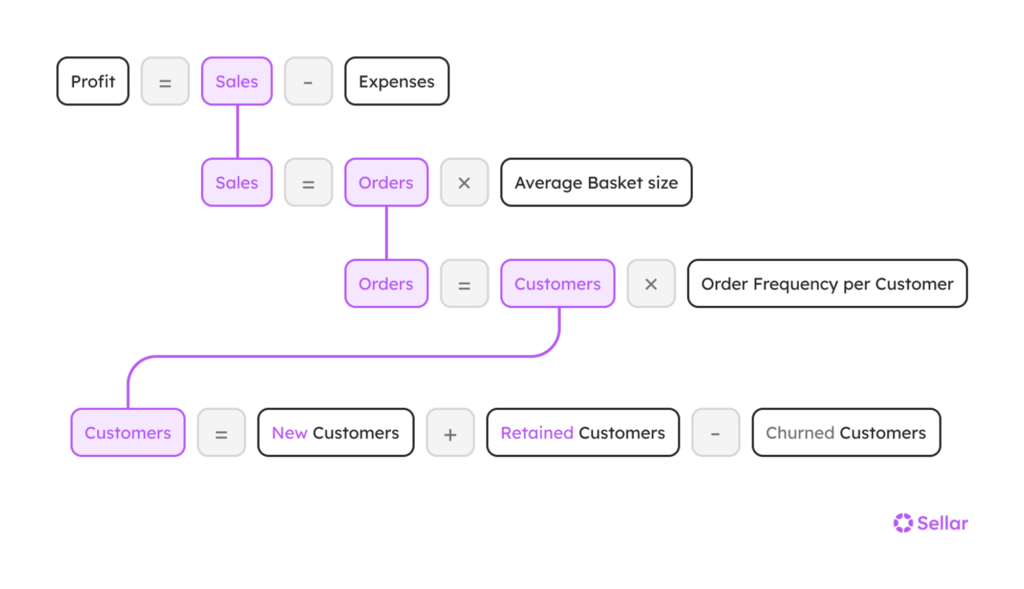

Given its relationship with Orders and Sales, it goes without saying that the number of customers you have is an incredibly important KPI. Most want this number to be as big as possible. Inflating the number through a lax definition might make us feel better about ourselves, but that doesn’t help us to grow profitability or sales.

In tough times, we can’t afford to drink our own Kool-Aid, so let’s get specific with how we define customer. This will help us go from a ‘vanity metric that strokes our ego’ into a ‘useful KPI we can use to improve our business’.

So… define customer…

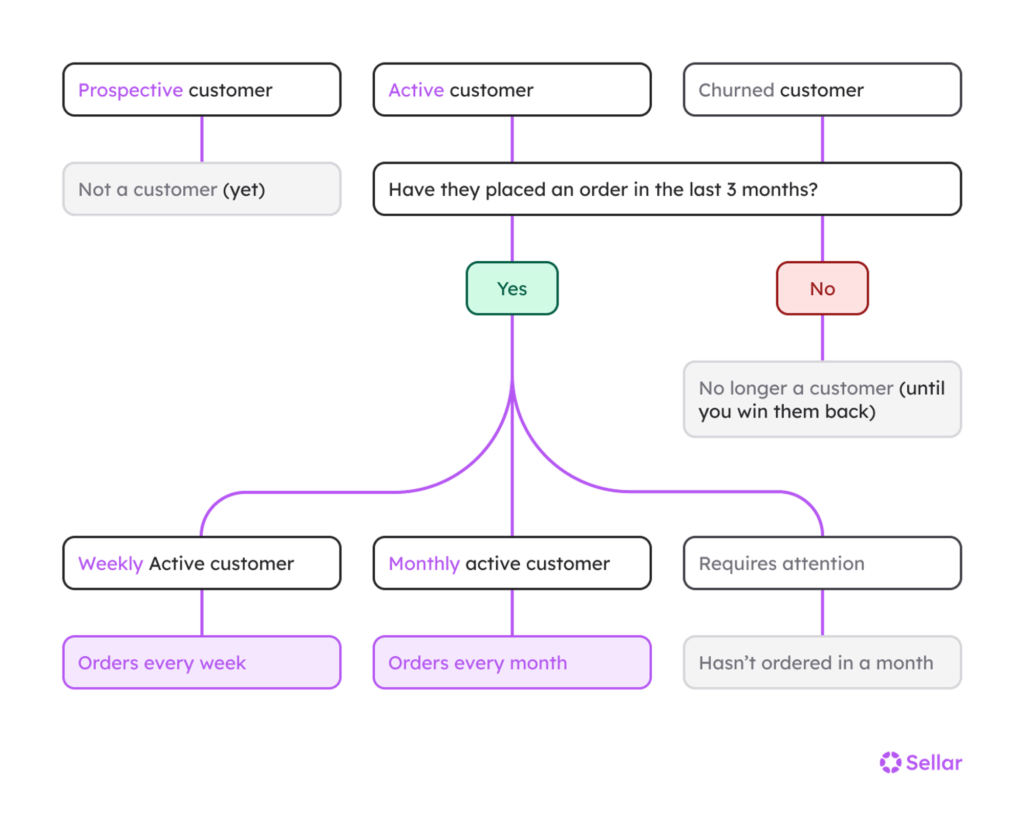

A customer isn’t someone who might one day order from you. And it’s certainly not anyone who’s ever ordered from you. So when does someone become a customer and when are they no longer a customer?

Prospective customers are not customers yet. Obviously. Once they make a purchase they become a customer, but for how long?

There aren’t many things that feel as good when a new customer buys from you for the first time. But, there are two paths from this point:

- That customer never buys from you again.

- They become a customer for life.

Plus everything that exists in between.

Is that customer ever going to buy from you again? What can you do to make sure they do? Unfortunately, you can’t control buyer behaviour. But you can influence it by doing everything in your power to ensure you’ve given that buyer the best experience possible.

But let’s say you forget about them, and move on to the next shiny new prospect. How much time needs to lapse before you need to update your relationship status from ‘customer’ to ‘*ex-*customer’?

This is subjective and can depend on details such as the industry you operate in and even your strategy.

Personally, I think the most appropriate time frame for the brewing industry is 3 months.

This 3-month time frame presumes that you’re focused on building strong relationships with your trade accounts. If your customer base tends to be more rotational, it might make sense to increase this time frame. The important part is identifying the accounts that might need attention and what structures you can put in place to grow sales from your existing customer base.

Of course, you could continue to break this down further. Ultimately, it depends on what you see as success for a given channel or customer type. The ordering habits of distributors and export customers will look different to indy bottle shops.

However, be wary of going beyond the point of exceedingly specific. Your numbers will become harder to track. This makes it harder to know if the effort you and your team are putting in is influencing your KPIs in the right direction. Which is what this is all about.

Now we have a definition. We can focus our attention on improving our KPIs and taking our business to the next level.

Improving these variables will increase our sales →

Basket Size

Order Frequency per Customer

New Customers

Retained Customers

A small percentage increase in each variable can have a huge impact. For example, let’s say a new brewery that’s doing about £10k per month in sales was to increase their basket size by 5%. That’s an extra £500 each and every month. It’s probably worth investing some time into figuring out how you can achieve this. Especially as your trade sales grow. Let’s say you’ve gone from doing £10k per month to £100k per month, that’s an extra £5k each month. Not bad.

At this point, you might be asking: “So can I just focus on improving each of those KPIs and I’ll build a successful and profitable brewery?!”

Not quite.

Yes, acquiring new customers, getting them to not only order more, but order more often, AND keeping as many of them as possible for as long as possible is a huge part of the battle. Probably better described as a never-ending journey.

Making those improvements will increase your customer LTV → Lifetime Value. One of the fundamental KPIs I mentioned at the start.

But it’s only half of the battle. It’s the Sales half. What about the Expenses half?

Without understanding your CAC → Customer Acquisition Cost, you can’t be sure that you’re building a profitable business rather than simply growing volume.

Our research shows the average CAC in the brewing industry at the moment is £379. But is that good or bad?

The answer entirely depends on your LTV. It’s essential to make sure your CAC < LTV. But that’s a whole other post…